Turkish is a fascinating language, and a challenge for the well-meaning holidaymaker

who thinks to pick up a little for the sake of international goodwill. One of

its peculiarities is a feature known to linguists as agglutination, whereby

grammatical functions are constructed by adding suffixes to a lexical root.

There is in theory no limit to the number of suffixes that can be agglutinated,

and Turks take pride in the following word: 'Çekoslovakyalılaştıramadıklarımızdanmısınız?'

which has eleven suffixes, and can be rendered into English as 'Are you one of those whom we have been

unable to make Czechoslovakian?'

Of course every country and culture likes to feel that it is the best at,

or has the biggest, longest, whatever, of something - it's a natural human (or

at least a male) thing. So as native speakers of English, we understandably

dredge our memories for the longest word we know - and maybe come up with 'antidisestablishmentarianism'. It doesn't quite measure up, but it does at least have a useful and significant meaning (unlike its longer Turkish counterpart): ‘opposition to the disestablishment of the Church of England.'

Why am I telling you this? Because ‘establishment’

in this context means that Anglicanism is the official state religion of

England, which, in turn means that England is not strictly speaking a secular

state. The main precedent for this is the adoption of Christianity as the state

religion of the Roman Empire by the Emperor Theodosius I in 380 CE. You might

think that the world has moved on a little in the intervening 1630 years, but

the English Parliament (wherein twenty-six seats are reserved for senior bishops) is

holding the line.

What got me thinking about this was the recent election of a new Pope to

preside over the international community of Roman Catholics - more

specifically, a couple of discussions that surfaced in a circle of history

buffs I follow online. The first was prompted by someone asking the question: “If Benedict XVI

was not the most intelligent head of state ever, who was?” Now I have to confess, it’s not a question that would

ever have occurred to me – not least because I never really think of high

intelligence as being a major requirement for a head of state. Nevertheless,

once the question was posed, it got me thinking. Is being highly intelligent

compatible with being a Catholic? Is the Pope actually a head of state?

|

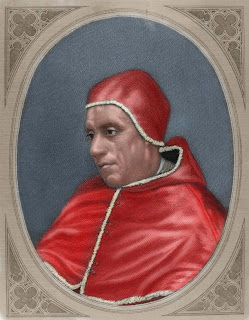

| Pope Gregory XII, resigned 1415 |

Well, probably the second question is the easier of

the two, so let’s look at that one first. It seems that international law gives

diplomatic recognition to two institutions of the Catholic Church: the Holy See

and Vatican City. The latter, I was interested to learn, was actually established as an independent state by an agreement, in

1929, between Pope Pius XI and Italy’s ‘Duce’, Benito Mussolini. According to Wikipedia, “Vatican City is an ecclesiastical or sacerdotal-monarchical state,

ruled by the Bishop of Rome—the Pope. The highest state functionaries are all

Catholic clergymen of various national origins. It is the sovereign territory

of the Holy See (Sancta Sedes)

and the location of the Pope's residence, referred to as the Apostolic Palace.”

If that sounds positively archaic to you, it’s not surprising. A ‘See’ in RC parlance was originally the

chair in which a bishop sat, but has come to mean the area over which the

seated bishop has episcopal authority. Twelve of these gentlemen are said to

derive their authority from an unbroken succession going back to Jesus’s twelve

apostles. One of them, The Holy See, claims pre-eminence on the basis of

direct descent from St Peter himself, and its official existence seems to date

from some time in the 5th century.

Fine and dandy. I have no problem

with Roman Catholics adhering to whatever beliefs give them comfort in the long

dark teatime of their souls. Only I don’t quite understand why they get to have

international recognition of statehood on the basis of their strange beliefs

and their Pope's alliance with a fascist Italian dictator in the 1920s. If

Catholics, why not Presbyterians? Which brings me to the question of

intelligence – and I suppose you’d have to admit that people who can pull that

kind of stunt on the international community must be pretty smart characters.

It’s self-evident that you do

need some kind of smarts to get yourself elected or appointed to a leadership

role at that level of society. After all, the Roman Church does claim to have 1.2

billion adherents, even if 1,199,999,880 of them don’t actually have any say in

choosing the new fella. But as for intelligence, that’s a curly one. IQ

(Intelligence Quotient) used to be thought of as a way of measuring human

intellectual capacity, but has gone out of favour in recent years. Former world

chess champion Bobby Fisher (IQ 187) probably contributed to that as his genius

for chess descended into vitriolic diatribes against the United States and the

Jewish people. These days most discussions of intelligence recognize nine

different types, one of which, linguistic, may be what Benedict XVI had.

The big thing for me is that

intelligence can’t exist in a vacuum. It manifests itself in outcomes, and from

those we will judge the mental capabilities of the individual. So it seems to

me we can look at the ex-Pope’s intelligence in three ways. First, the guy is

undoubtedly smart, and, discounting Tony Blair’s miraculous conversion, I

reckon it must be pretty tough to be intelligent and to believe all that stuff

that Catholics are expected to believe. So full points to the ex-Holy Father

for being able to compartmentalize knowledge, if that’s what he did. On the

other hand, it may be that early in his academic life, Joseph Aloisius

Ratzinger decided that he wanted power, and thought the Church was a good

career path, so he mouthed the mumbo jumbo in order to get where he wanted to

be – another sign of a certain kind of intelligence, for sure. Then there’s the

fact that Benedict resigned – the first Pope to do so since Gregory XII in 1415.

Undoubtedly, for believing Catholics it’s a disappointment, and not at all the

done thing – but in the greater scheme of things, we may think Father Joseph

finally saw the error of his ways – and being able to admit your mistakes may be a another indicator of intelligence.

That last comment may seem unduly

harsh, but take a close look at the history of Roman Catholicism and you’ll see

what I mean. Here I want to touch on the second topic being

discussed by my online friends, which involved some scholarly debate on the

definition of 'heresy', and whether

it differed from 'dissent', in the

context of Christianity. In the course of my Euro-centred Christian-oriented

education, I learned that the early followers of Jesus were strong-minded

innocent souls suffering terribly at the hands of Roman Emperors, who employed

various methods, of which feeding to lions was a favourite, to discourage the

spread of the new religion. What I didn't learn until much later was that, once

those Roman Emperors, for reasons of their own, which may or may not have had

much to do with actual spiritual experience, decided to 'establish'

Christianity as the state religion, the apparatus of institutional persecution

was turned on those who failed to toe the official Christian line.

The process, essentially was this: the emperor and his

sacerdotal henchmen gathered together in various ecumenical councils, most of

which were held within the territory of the Eastern or Byzantine Roman Empire

(in modern Turkey) and formulated a doctrine, or set of articles which would

thereafter be required beliefs for 'orthodox' Christians. These councils, by

the way, were convened 300 years or more after the death of the church's

namesake. The articles of 'faith' were designed to include elements which made

it relatively easy for adherents of earlier pagan and folk religions to find

points of contact with the new official system, while, at the same time,

provided a basis for getting rid of troublesome parties who might foster

dissent from within. The result was a creed, or creeds, containing 'truths'

never claimed, as far as I am aware, by Jesus himself, and closing debate on matters

that a reasonable human being might consider highly debatable, even irrelevant

to the essence of the business.

As an illustration of this, let me include an excerpt

from the Athanasian

Creed, which came into use in the 6th century, and is apparently still, I

understand, subscribed to by mainstream western Christian churches, though,

perhaps understandably, no longer much used in everyday worship:

“Whosoever will be saved, before all

things it is necessary that he hold the catholic faith; Which faith except

every one do keep whole and undefiled, without doubt he shall perish

everlastingly. And the catholic faith is this: That we worship one God in

Trinity, and Trinity in Unity; Neither confounding the persons nor dividing the

substance. For there is one person of the Father, another of the Son, and

another of the Holy Spirit. But the Godhead of the Father, of the Son, and of

the Holy Spirit is all one, the glory equal, the majesty coeternal. Such as the

Father is, such is the Son, and such is the Holy Spirit. The Father uncreated,

the Son uncreated, and the Holy Spirit uncreated. The Father incomprehensible,

the Son incomprehensible, and the Holy Spirit incomprehensible. The Father

eternal, the Son eternal, and the Holy Spirit eternal. And yet they are not

three eternals but one eternal. As also there are not three uncreated nor three

incomprehensible, but one uncreated and one incomprehensible . . . . So that in all things, as aforesaid,

the Unity in Trinity and the Trinity in Unity is to be worshipped. He therefore

that will be saved must thus think of the Trinity.”

Says who? you may ask. Well, I have to agree, you need

a certain kind of intelligence to get your head around that, or even to want to

think about trying. You might also suppose the word 'incomprehensible', included five times in that text, and rightly

applied to any entity worth worshipping as GOD by an intelligent human being,

would let you off the hook - but not so. Those words were carefully and

specifically chosen to allow authorities to weed out deviants from the true

path. The Wikipedia entry on heresies

lists fifty-four distinct ideas that have qualified as such over the years

under 'established’ church law, the most recent of which involved a

nonagenarian lady in Canada whose followers believed she was a reincarnation of

the Virgin Mary, and were duly excommunicated by the Pope in 2007. Early

heresies tended to focus on what Jesus actually was, given the church's

insistence that his mother was a virgin and his father was the Lord God

Almighty. Clearly an incomprehensible God would need an equally

incomprehensible agent to carry out such worldly activities, hence the Holy

Spirit (or Ghost, if you prefer). Then the debate tended to get

entwined in arguments over whether Jesus's body was actually like yours and

mine, or made of some less corporeal stuff; whether he had a normal soul like

other mortal men; and whether there was some kind of divine substance in there

too, setting him apart from the rest of us.

The consequence of all this was the establishment of a

state religion with a very strict code of 'beliefs', and the expulsion,

excommunication and persecution of dissenters from the party line (labeled heretics, which has a more resonant ring

to it, the better to justify punitive action). The big winner was the Roman

Empire, by this time, centred on the eastern capital of Constantinople,

especially after the fall of western Rome to the barbarians in 476 CE. It's

also pretty obvious that most of the early action in the birth and evolution of

Christianity took place in eastern lands, with the West a relative latecomer on

the scene.

Still, once they got going, Western Christians set

about making up for lost time. Early convocations of bishops formulating the creeds

of the established church took place in eastern cities, Nicaea, Chalcedon and

Ephesus, and you couldn't really deny their conclusions without getting

yourself out on an insecure limb. What you could do, however, was sneak an

extra word or two into the text (in Latin so the ordinary Joe wouldn't notice),

then, when the time was right, insist that your version was the correct one,

thereby creating a doctrinal split, giving you grounds to excommunicate the

other side and set yourself up as the true church. Which is more or less what

the Romans did. It's known in theological circles as the 'filioque' controversy, and relates to a word

inserted into the 4th century Nicene Creed in Spain some two centuries later.

By the 11th century, Western Christendom felt itself strong enough to challenge

Constantinople for supremacy, and that word provided doctrinal justification

for the Great Schism of 1053.

Not long after, in 1071, Seljuk Turks defeated the

Eastern Romans in battle and began serious incursions into territory

long-considered part of the European sphere of influence. Pope Urban II's launching

of the First Crusade in 1096, and subsequent Crusading invasions by armies from

Western Europe may have been ostensibly aimed at freeing the so-called Holy

Lands from the clutches of Muslim unbelievers; but subsequent events suggest

that uniting Europe under Papal and Roman Imperial authority played a major

part; as did a desire to expropriate and/or plunder wealthy eastern lands and

cities; and to demonstrate to Eastern Christians where the real power in

Christendom now lay.

Things didn't work out exactly according to Papal

plans, of course. The Holy Roman Empire never really got off the ground.

The Byzantine Empire fell, but to the

Ottoman Turks. It was another five centuries, nearly, before those Holy Places

returned to Western control, by which time they had been in Muslim hands for

most of the previous two thousand years, and continue to cause severe headaches

for all concerned.

Nevertheless, the Roman Catholic Church had

'established' itself as a dominant player in European power games by the

beginning of the second millennium, and the concept of heresy was the major

tool in its box of tricks for ensuring compliance. It was obvious to many, even

in those days, that the search for temporal power had resulted in an organizational

structure that had more interest in matters material than spiritual. For four

hundred years before the successful emergence of Protestantism in the 16th

century, various groups (Cathars

and Waldensians in France, for example) were challenging the materialism of the

established Roman Church, and being viciously suppressed for their idealism.

The Inquisition was not a peculiarly Spanish

invention, but it achieved notoriety during the 15th century as the

mechanism whereby the Iberian Peninsula was ‘reclaimed’ for Christendom.

Muslims and Jews were forced to convert or leave, and the backsliding converted

were ruthlessly hunted out. Some modern Catholic sources suggest that there

wasn’t as much burning at stakes as we had been led to believe – but the

existence of the threat may have been enough to overcome the reluctance of

some; and if not, there were less fatal but nonetheless exemplary methods of

persuasion, among which foot-roasting was apparently popular.

An interesting concept I came across recently is

something referred to in RC literature as ‘The Black Legend’, which

argues that most of that Inquisitorial unpleasantness didn’t actually happen,

and that stories about events in Spain and Spanish conquests in Central and

South America were concocted and spread by Protestants keen to discredit their

religious rivals. To me it sounds rather akin to Holocaust Denial. What was

the reason for all those Spanish Jews uprooting themselves from their homeland

of centuries and resettling thousands of kilometres away in the Ottoman Empire

in the 1490s? Maybe they just felt like a change of scenery?

As we head into another Easter weekend, I find myself

wondering again about the strangeness of that central event in the Christian

calendar. As far as I can learn, the First Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325

CE determined the date of Easter to be the first Sunday after the full moon

following the March equinox, which is why the holiday moves around from one

year to the next (a moveable feast, in technical parlance). But you’d want to

ask, why would they do that? If you’re commemorating the date Jesus Christ was

crucified, why not go for the actual date, or at least fix a date and run with

that? Could it have been that a lot of the local populations were partying up

large at spring fertility or seed-planting celebrations and the Jewish Passover

at that time of year, and the machinery of state decided to make a virtue of

necessity? If you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em, and then gradually shift the

official emphasis. Makes a lot of sense.

Similar theories have been advanced as origins for the

stories of Jesus’s virgin birth at the winter solstice, his crucifixion and

resurrection at the spring equinox, and the cult of his mother, Mary. Just down

the road from the supposed House of the Virgin Mary near the town of Selçuk in

Aegean Turkey are the remains of the classical Temple of Artemis, one of the

Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. The Greek goddess Artemis is linked to the

Phrygian female deity Cybele, and the generic Anatolian mother goddess.

Virginity was one of their characteristics, as was, paradoxically, a quality of universal

motherhood. Associated with Cybele was a young man, Attis,

born to a virgin mother who may or may not have been Cybele. Whatever the case,

week-long festivities in their honour were being conducted well into classical

times, and may have inspired those early church authorities to add sympathetic

embellishments to their own creeds.

Well, who knows? It’s all too long ago for anyone to

be able to demonstrate sure proof of what actually went on. What we can say with

some certainty is that a good deal of what passes for Christian ‘belief’ was

determined by power-hungry gentlemen in days of old with very secular imperial

aspirations, and a fair amount of rather nasty coercion was applied to ensure

that dissidents were silenced or removed to a safe distance. That’s the reason

that 'disestablishment' movements have constantly resurfaced over the centuries.

In the end, the search for truth starts and ends in your own heart. If the new

Pope's ok with that, then I'm ok with him.